I am Not Fucking inTerested in NFTs, nor the hyperbolic discourse that has emerged around them in recent months, as I’m sure by now neither are you. Are NFTs democratising digital ownership? Are they enabling creators to cash in on their influence? Is this a new creative economy? Is this the Future of Art™?

I have very little interest in attempting to answer these questions, which I believe to be purposefully loaded and essentially bad faith. I am very interested, however, in the ways that platforms & contexts impact creative output and vice versa - from the totalitarianism of millennial minimalism to the consciously conditioned ‘chaos’ of the Gen Z aesthetic playbook. When it comes to good ol’ non fungibles, I’m more concerned with the big hitting questions, such as: why do all NFTs look like that?

[Beeple exhibition, shared by Vox]

The aesthetic of a typical NFT is something like this: slick, 3D, weightless, consciously digital, elaborately textured, futuristic, retrofuturistic, manufactured, fractured, glitching, abstract, illuminated, lucid, looping. It’s not for nothing that these words are easily converted into hashtags, optimised for an online marketplace.

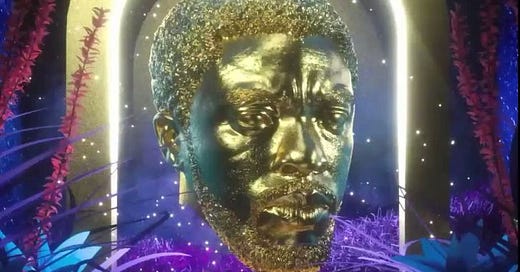

The recent Chadwick Boseman NFT by artist Andrea O’Shea, controversially given to Oscar attendees in their gift bags this year, is a stereotypical example of the visual genre:

Gold! Ferns! Stars! Plinths! 360 degree rotation! Lo-fi hip-hop beats!

NFTs are art for an age in which artists are ‘creators’ and art is ‘content.’ They are a self-conscious flex of the animator’s standard Adobe plugin toolkit: drop shadows, bevelling, rotated light sources, texture packs etc. They’re iOS desktop backgrounds or elaborate fancam edits made by dexterous teenagers.

They look like something you’d be served on your Instagram explore page by one of those weird Russian bot accounts that post looped 3D ASMR animations they’ve ripped from Pinterest. They look like an asset you might feasibly have outsourced from an underpaid subcontractor three timezones away on Fiverr (it’s almost too perfect that the Boseman NFT licensed a pre-existing model of Chadwick’s head rather than make one from scratch).

The art analytics blog ArtNome shared a handy graph that compared NFT views vs sales price on marketplace SuperRare, in a post that investigates the relationship between online influence metrics and market value. (Hint: they’re more than a little related.) It’s a really great piece of research and you should read it. But what I was personally fascinated by was the particular use of descriptive tag, which reinforced my suspicions about the prevailing NFT aesthetic:

‘Trippy’, ‘render’, ‘surreal’, ‘scifi’, ‘3D’ - @jerrysaltz will soon be out of a job!

So why is the aesthetic of NFTs significant? (They’re investment vehicles for financial speculation and money laundering! Their look is essentially irrelevant!) There are a few reasons why I think considering their appearance still holds value:

It represents a collective effort to imagine what the future might look like.

It’s a way of understanding who they serve and what they stand for.

It’s an angle that think pieces haven’t done to death already (only - partially - joking!)

NFTs have been pitched as rebellious, democratising, antiestablishment, empowering, an iconoclastic fuck you to the gallery system, etc etc. The pro-NFT argument claims that they are widening access to the arts, allowing artists to paid fairly, and introducing a new generation to the industry: ‘Now people from all economic stripes, from every class of society and every social, political, and economic background are able to access the same people on a very simple-to-use medium,” argues curator Kenny Schachter, somewhat unconvincingly.

Others argue that NFTs don’t actually do any of those things at all. They state that NFTs represent a fiat currency, a bubble of tulip proportions, a replication of the same access restrictions and lack of transparency they claim to combat. Everydays—The First 5,000 Days, Beeple’s $69.3 million record breaking NFT collage, was sold by Christie’s after all. Oh, and they’re also destroying the environment.

This tension is dramatised by the aesthetic of NFTs.

If artists’ exhibition space is now a platform and thus governed by platform logic, NFTs become subject to the same struggles that entangle social media more broadly: where does power lie, who controls the conversation, how democratising is the demotic turn, etc. Under these conditions the aesthetic of the NFT becomes something more than just simply decorative: a symbolic battle between culture and counter culture, corporations and individuals, platforms and participants. The prevailing aesthetic of the NFT can therefore add something to the conversation about their use and value.

Let’s return to the Chadwick NFT for some art history 101. Breaking down the aesthetic influences of a 15-second animation of a late Hollywood actor’s head isn’t the way I imagined my Sunday bank holiday evening to go, but here we are.

[Alexis Christodoulou]

Influence #1 - Soothing spaces: This isn’t an authorised term but I’m not sure what else to call this odd product of the last 5 years on social media. There’s an Instagram ‘3D artist’ genre consisting of dreamlike architectural nowheres (liminal spaces are themselves a particularly internet obsession, thanks Reddit!), repetitive motions, and soothing pastel palettes. Related are the looping animations shared by Calm or other mindfulness apps and accounts marketed towards anxious millennials. Brands have since adopted this visual environment to flog products from a futuristic wellness angle - this Fenty example of a moisturiser scoop was shared with me today, Dezeen report on TBWA’s "soothing and hypnotising" animations of McDonald's Egg McMuffins. These aesthetic influences are seen in O’Shea’s use of plinths, curved archways, and seamless muzak beats. They’re also widespread across NFTs in general.

Influence #2 -‘Net art’ & ‘post net art’: I really hate to categorise all net art as having a unified aesthetic, but Rhizome said it was ok. (I curated 2 shows of internet art in the mid 2010s under the moniker g_URL so I feel vaguely qualified to make this sweeping generalisation). The net art aesthetic is inherently metatextual, appropriating and undermining the functionality of technology to collapse content with the network within which it has been conceived. It’s very Marshall medium-is-the-message stuff. Lots of 3D renders, VR art, immersive worlds, organic shapes (eg petals or natural elements) recreated in virtual contexts. You can clearly see the net art influences on the Boseman piece and NFTs in general - they’re often deploying tech for tech’s sake, ‘showing the working’ using wireframes or 360 degree render rotations, and sometimes including more literal elements such as browser bars/windows/other internet vernacular.

Influence #3 Vaporwave: I guess it’s time to admit I have a huge soft spot for Vaporwave bc it was the prevailing #aesthetic when I joined Tumblr back in the late 00s/early 2010s. Vaporwave was a subcultural movement that satirized consumer capitalism and yuppie culture via remixed corporate muzak and the appropriation of early technocapitalist iconography - Internet Explorer icons, browser menus, and pixellated cursors - along with web 1.0 design elements and TRON-like digital landscapes. The colour palette of this movement (purples, blues, pinks, neons - an early iteration of bisexual lighting), its combination of organic and inorganic materials, incorporation of classical mythology, glitch effects and fractal-like patterning are all present both in the Boseman NFT and in NFTs more generally.

So what do these visual signifiers tell us about NFTs?

The mingling of these various influences within the aesthetic of the NFT tells us, on a merely functional level, that they’re the product of the internet; an algorithmic amalgamation of popular genres and trending content. But they also illuminate the struggle between the internet’s ability to cultivate subcultural groups and the subsequent commodification of those groups, escape from capitalist conditions and the intensification of those conditions thanks to the internet.

These aesthetic signifiers seem to highlight NFT’s own struggle with self-definition: consciously, or subconsciously, adopting and developing aesthetics which represent ongoing sites of contest. Soothing spaces offer exhausted workers relief from overworked, atomised, precarious states of existence, but they are also tools used to sell us products and flog self-soothing back to us as a $$$ service. Vapourwave was a form of early aesthetic resistance to the corporate internet: now it’s a million dollar NFT. NFTs are ‘democratising’ art and ownership whilst simultaneously reinforcing the value of ownership and concentrating IP and revenue in the hands of a few.

This is a similar dynamic to January’s GameStop saga, hailed as a victory of the man on the street against the financial establishment, but which doesn’t represent the democratisation of stock market trading but the further entrenchment of market principles and the inflated valuation of its investment funds. (Personally, I think the answer to attribution and ownership in the digital age isn’t to financialise the process of acquisition/distribution. But this really isn’t my area...)

If the aesthetic of individual NFTs is one way of exploring where they fit within platform capitalism, then the same applies for their own platforms too. Look at the way that Foundation, the first and largest NFT marketplace, market themselves.

Foundation bridges crypto and culture to create mutual support between artists and collectors. We’re forging a community-driven path, providing culturally pioneering curation, and sharing our tools with the rapidly evolving community of developers who are excited to define this future with us. We want anyone and everyone who cares about the future of digital expression to be a part of it. Let’s explore these new possibilities collectively.

With full bleed gradients, left-aligned text, and mixed type treatment (deliberate asymmetry between an old-school, serif style font mixed with kooky, tech inspired type - hands up I’m guilty of this formula!), they are indistinguishable from a trendy DTC lifestyle brand that’s adopted a streetwear ‘drop’ style model to drive ‘consumer hype’ and has managed to snag $5m VC funding in the process:

Foundation is a system for value extraction dressed up as a creative community of like minded individuals, a marketplace branded as an edgy, independent collective.

I’m completely fascinated by the ways in which capitalism has appropriated the aesthetics of individual artist creativity (e.g. Ogilvy’s new website looks like a trendy East London based design studio, or the newly rebranded CIA logo which creative director Ryder Ripps pretended to have produced), and the ways in which independent artists have reclaimed corporate aesthetics in return (‘corporatecore’ needs to be addressed in a different post - I hate myself for how much I want a Lehman Brothers hoodie).

I guess the middle ground between these two aesthetic extremes - ‘corporate’ and ‘creative’ - is an ‘anti-aesthetic’ (a concept riddled with problems in itself, can you ever create an anti-aesthetic on the internet without it being commodified?). But don’t worry, NFTs are anti-aesthetic too.

Not all NFTs are the smooth, slick, lucid 3D render of the Boseman piece. Others are crappy clip art, glitchy GIFs, crunchy screenshots and jarring Photoshop jobs. See Chris, one of the top creators on Foundation:

This style of NFT, along with other kinds of meme, is both popular and valuable:

2005 meme ‘disaster girl’ sold for $500,000

2011 meme Nyan Cat sold for $600,000

2012 meme ‘overly attached girlfriend’ sold for £335,000

Even the most anti-commercial, anti-corporate, anti-aesthetic form of artistic expression, the meme - a lo-fi, low-res, lossy, crude clip-art form of low-brow cultural communication - can be wrung through the million-dollar NFT machine and emerge a valuable asset. This is the NFT effect. No subculture is safe.

The meme as poor image, as black, operates against the rich image: the full-bodied high-res representation for which identity politics and visual theory taught us to strive. The meme is always writing and rewriting itself, operating, as Steyerl writes, “against the fetish value of high resolution.” - Aria Dean for Real Life

Tangentially, I’ve been tracking the meteoric rise of one particular meme account, @afffirmations, over the past few months. Their posts look like this, and their account has shot from 94k - 300k in around eight weeks:

They use clip art, stock images, lurid drop shadows and deliberately ironic aphorisms to satirise typical Instagram hustle and wellness content. At some point I might do a deep dive on this trend and what it means. But for now, the account’s rapid elevation clearly indicates some audience thirst for awkward, anti-commercial output - the opposite of a smooth ‘soothing space’ or branded Instagram infographic. Personally, I love it. In its own small way, it’s a form of aesthetic resistance to the smooth commercial world of professionally-produced brand content, polished and BVI-compliant. Unfortunately, it’s exactly the kind of thing I can imagine as an NFT.